Hands-On, Minds-On: Engaging Students Through Active Learning

What Is It?

A wide range of studies suggest that merely exposing students to information does not stimulate deep, meaningful, or lasting learning. Students need to cognitively process course content in order to successfully comprehend, retain, and ultimately apply what they learn. Deeper levels of processing, including those that focus on meaning-making, tend to be the most effective in creating new memories (Craik, 2021; Craik & Lockhart, 1972; Craik & Tulving, 1975; Hyde & Jenkins, 1973). This is why prompting your students to process the information they encounter in your course is critical to their success.

There are probably several ways in which you currently prompt your students to think about course materials, which means you are already using active learning. The term active learning has been defined as “classroom strategies that move away from a transmission or ‘telling’ model (the classic ‘didactic lecture’) toward a model where students actively engage in problem-solving and knowledge creation” (Apkarian et al., 2021). Such activities generally call for higher-order processing of materials, such as analysis, synthesis, or evaluation (Bonwell & Eison, 1991, p. 2; Doolittle et al., 2023).

What Does It Look Like?

One commonly used active learning exercise is called Think-Pair-Share. Students are provided with questions or problems related to the materials they study, and they are asked to think about those prompts as they grapple with the information. They are then paired with a classmate to share and refine their understandings. Finally, the instructor conducts a whole class discussion in which pairs of students share their insights while the instructor synthesizes key themes.

Think-Pair-Share is designed to be integrated with student exposure to course content, whether during class or while completing homework. If the homework involves reading, for example, students may be given prompts before they do the reading. Below is an example of a Think-Pair-Share for a U.S. History class that was integrated with the week’s reading assignments. Students were asked to consider the prompts as they did the readings and make note of their responses. This turned a typical homework assignment into one that stimulates active reading.

Think-Pair Share Activity: U.S. History Through 1865

Write-to-Learn & Peer Review Activity: Foundational Biology

Muddiest Point Activity: College Algebra

Does it Work?

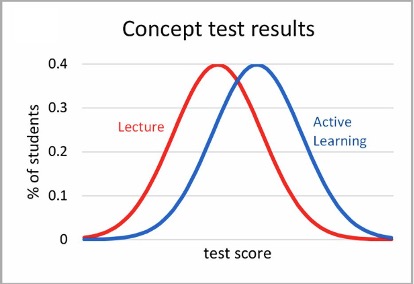

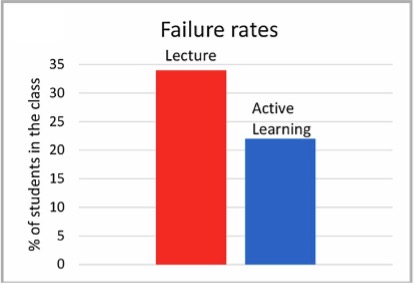

Students in classes that apply active learning perform substantially better on conceptual tests than those in lecture-based classes (Freeman et al., 2014, Kozanitis & Nenciovici, 2022, see Figure 1 for results in STEM fields). They also have dramatically lower failure rates (see Figure 2). A study by Ballen et al. (2017) suggests that the performance gap between students traditionally underrepresented in STEM fields can be closed with the application of active learning.

Fig. 1: Meta-analysis of conceptual test scores in STEM fields (data from Freeman et al., 2014; visually adapted by Wieman, 2014).

Fig. 2: Meta-analysis of failure rates in STEM courses (data from Freeman et al., 2014; visually adapted by Wieman, 2014).

There is also extensive research into the impact of active learning on student engagement. A study by Lombardi and Shipley (2021) suggests that active learning increases engagement across several dimensions:

- Social-behavioral: Participation with classmates in learning activities

- Cognitive: Focus during activities, application of learning strategies, and self-regulation

- Emotional: Enjoyment of the learning experience and feelings of belonging

- Agentic: A sense of ownership of their learning path and self-identification as constructors (and co-constructors) of knowledge (Lombardi & Shipley, 2021)

These are just some of the broad range of findings that demonstrate substantial gains for students through the application of active learning.

How Do I Do It?

You can address a range of levels of complexity and depth of understanding using active learning. Simpler activities, such as Think-Pair-Share and Muddiest Point, can be used frequently to prompt routine reflection during classwork and homework. Instructors often integrate them into the instructional routines of their courses. More complex activities with multiple steps or extended classroom interactions can be used on an intermittent basis to support deepening and synthesizing of student knowledge.

We recommend you start by adding one of the simpler activities to a single meeting of your class and/or the relevant homework. Use any of the three examples shown above as a model for the new or revised activity. There is a great deal to be gained from regular integration of simple active learning strategies, prompting students to mentally process materials as they engage with them.

As you add activities, students may notice a shift toward greater involvement in their learning process. To ease the transition, begin with an explanation of the value of active learning and how it benefits students (e.g., deeper understanding, better retention, more interaction with you and their peers). Clarify what participation looks like and how it connects to course goals and assessments. To develop common ground, you can guide students through an overt process of establishing community agreements early in the course.

Reinforce the initial guidance you provide by checking in with students early in the term. Students need to develop and apply relevant communication and teamwork skills, making space for equal participation while also respecting a diversity of views. Scaffold the development of these skills by starting with low-stakes, simple formats, like Minute Papers or Think-Pair-Shares. You can then gradually introduce more complex or collaborative strategies as students become more comfortable with these learning structures and as they acquire the knowledge needed for intermediate or advanced work.

As you gain confidence and facility with integrating active learning in your class, you can consider more complex active learning strategies, particularly for larger assignments or projects students complete. Below are several examples of more complex assignments, including a Jigsaw Activity and a Case Study.

Jigsaw Activity: Social Psychology

Case Study: Health Assessment (Nursing)

For these activities, it is important to build toward them throughout the semester with smaller exercises and assignments. As an example, the Nursing Case Study involves application of health assessment frameworks. The instructor could assign materials and previous work that involves identifying and defining those frameworks, perhaps beginning with a quiz and following with a Peer Interview activity. Students also need to know how to correlate patient symptoms with assessment priorities, which could be addressed through smaller exercises that involve just that step – perhaps a quiz followed by one or more Think-Pair-Shares. In this way, students scaffold toward more complex active learning activities through multiple simpler ones.

We hope the above steps will guide you as you begin adding active learning elements to your course(s). As you progress, you may also wish to consider this set of ten implementation guidelines.

Can I Get Help?

Absolutely. When selecting or designing activities, whether simple or complex, it may help to refer to any of these active learning resources:

- 40 Active Learning Strategies to Try: The section below this one in this document provides a categorized list of 40 Active Learning Strategies to Try, with concise descriptions of each; there is also a separate document with fuller descriptions of the same 40 strategies. Using either version, you can pick a category relevant to your course to peruse some of your options.

- Center for Teaching and Learning at UC Berkeley: Active Learning

- How to Shake Up Active Learning Assumptions (Harvard)

- Collaborative Learning Techniques: A Handbook for College Faculty

- Student Engagement Techniques: A Handbook for College Faculty

- Discussion in the College Classroom: Getting Your Students Engaged and Participating in Person and Online

For help at any stage, we also recommend contacting Teaching Support at the UNM Center for Teaching and Learning (teachingsupportctl@unm.edu). You also have the option to meet and discuss your activity with a CTL instructional designer at any of the regularly scheduled CTL Open Labs.

40 Active Learning Strategies to Try

There are many active learning strategies. To get a sense of the possibilities, select any category below.

✅ Notes:

S/M = Small/Medium classes

L = Large classes

✦ = Asynchronous online suitability

- One-Sentence Summary ✦ (S/M, L) – Students summarize key concepts in a single sentence. Helps with synthesis and clarity of understanding.

- Minute Paper ✦ (S/M, L) – Students write brief responses to questions such as “What was the most important thing you learned today?” Promotes reflection and identifies misconceptions.

- Claim–Reaction Note ✦ (S/M, L) – Students identify one claim, argument, or notable passage from the reading and write a brief personal reaction—agreement, disagreement, curiosity, or connection to another idea or context.

- Muddiest Point ✦ (S/M, L) – Students identify the part of the reading (or lecture) that was most confusing—the “muddiest point”—and write a brief note explaining what specifically they did not understand. Muddiest Points can be included at any point in the class. If done at the end of a class, they would be considered Exit Tickets, giving instructors the ability to clarify lingering issues when the next class convenes.

- Active Reading / Viewing ✦ (S/M, L) – Give students one or more focus question(s) and ask them to consider them while doing their readings or video viewings outside of class. You can also ask them to share brief responses to the prompts, in which case this becomes a Think-Write activity, or they can pair up with a peer to discuss to make this a Think-Pair-Share activity (see description in Small Group Collaboration section below).

- Self-Assessment ✦ (S/M, L) – Students evaluate their own understanding using rubrics or prompts. Encourages metacognition and self-regulation.

- Peer Teaching ✦ (S/M, L) – Students teach a concept to classmates. Builds mastery and communication skills.

- Collaborative Concept Glossary ✦ (S/M, L) – Students co-create a class glossary. Online tools enable asynchronous collaboration.

- Student-Generated Test Questions ✦ (S/M, L) – Students co-create exam questions and answers. Promotes engagement and comprehension.

- Peer Review ✦ (S/M, L) – Students critique each other’s work using rubrics. Encourages constructive feedback and reflection.

- Think-Pair-Share ✦ (S/M, L) – Students reflect individually, discuss with a partner, then share with the class. Builds participation and peer learning.

- Think–Write–Pair–Share ✦ (S/M, L) – Adds a written reflection before sharing, deepening thought. Works asynchronously in forums.

- Round-Robin Brainstorming (S/M) – Group members contribute ideas in sequence. Encourages participation from all.

- Snowball Discussions (L) – Pairs discuss, merge into larger groups, culminating in whole-class sharing. Effective for large groups.

- Peer Interviews ✦ (S/M) – Students interview each other on course topics and summarize insights. Can be done asynchronously online.

- Socratic Seminar (S/M, L) – Students engage in guided discussion exploring ideas deeply. Builds reasoning and argumentation skills.

- Literature Circles ✦ (S/M) – Small groups discuss readings with assigned roles. Online adaptation through forums works well.

- Fishbowl (S/M, L) – A small group discusses while others observe; roles rotate. Enhances listening and participation.

- Debates (S/M, L) – Students argue different sides of an issue. This activity encourages critical thinking and evidence-based reasoning.

- Case Studies ✦ (S/M, L) – Analyze real or hypothetical scenarios. May include or take the form of role plays. Enhances application and decision-making.

- Problem-Solving Workshops ✦ (S/M, L) – Students work through structured problems with guidance. Online, groups can post solutions asynchronously

- Application Papers ✦ (S/M, L) – Students write essays applying concepts to real-world contexts.

- Community-engaged projects ✦(S/M) – Connect coursework with community engagement. Reflections can be shared online.

- Gallery Walk (S/M, L) – Students circulate to view posted work or visuals and provide feedback. Promotes engagement with multiple perspectives.

- Interactive Timelines ✦ (S/M, L) – Students create visual timelines to organize events or concepts. Useful online with tools like TimelineJS.

- Concept Maps ✦ (S/M, L) – Students draw diagrams linking key concepts. Supports understanding of relationships and structure.

- Comparison Charts ✦ (S/M, L) – Organize similarities/differences in a matrix. Builds analytical thinking.

- Scavenger Hunt ✦ (S/M, L) – Search for examples or resources. Works asynchronously online.

- Crosswords / Concept Puzzles (S/M, L) – Reinforces key terminology interactively.

- Clicker Questions / Polls (L) – Instant feedback via polling in large classes. Not async.

- Interactive Textbook Engagement ✦ (S/M, L) – Some academic publishers have platforms that integrate student engagement with class readings, prompting students to think about the materials in various ways while reading. You can adopt this course-wide by selecting a textbook hosted on one of these platforms.

- Flipped Classroom Exercises ✦ (S/M, L) – Students review content before class, then apply knowledge.

- Shared Online Whiteboards ✦ (S/M, L) – Collaborative visual problem-solving online.

- Interactive Simulations ✦ (S/M, L) – Use tech-based simulations to explore complex systems.

- Digital Storytelling ✦ (S/M) – Students use multimedia for narratives.

- Think-Aloud ✦ (S/M) – Students narrate thought processes while solving problems. Works asynchronously via recorded explanations.

- Exam Wrappers ✦ (S/M, L) – Reflect on preparation, performance, and strategies post-exam. Encourages metacognition.

- Double-Entry Journals ✦ (S/M) – Students record quotes and reflections side by side. Enhances deep reading.

- Learning Portfolios ✦ (S/M, L) – Collect and reflect on work over time.

- Learning Contracts ✦ (S/M) – Students co-create learning goals and evidence of success. Encourages accountability.

References

Ballen et al. (2017). Enhancing diversity in undergraduate science: Self-efficacy drives performance gains with active learning. CBE-Life Sciences Education 16(4).

Bonwell, C. C., & Eison, J. A. (1991). Active learning: Creating excitement in the classroom. 1991 ASHE-ERIC higher education reports. ERIC Clearinghouse on Higher Education, The George Washington University, One Dupont Circle, Suite 630, Washington, DC 20036-1183.

Craik, F. I. (2021). Remembering: An activity of mind and brain. Oxford University Press.

Craik, F. I., & Lockhart, R. S. (1972). Levels of processing: A framework for memory research. Journal of Verbal Learning & Verbal Behavior, 11(6), 671–684. https://doi-org.libproxy.unm.edu/10.1016/S0022-5371(72)80001-X

Craik, F. I., & Tulving, E. (1975). Depth of processing and the retention of words in episodic memory. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 104. 268-294. 10.1037/0096-3445.104.3.268.

Doolittle, P., Wojdak, K., & Walters, A. (2023). Defining active learning: A restricted systematic review. Teaching and Learning Inquiry, 11.

Freeman et al. (2014). Active learning increases student performance in science, engineering, and mathematics. PNAS 111(23): 8410-15.

Hyde, T. S., & Jenkins, J. J. (1973). Recall for words as a function of semantic, graphic, and syntactic orienting tasks. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 12(5), 471-480.

Kozanitis & Nenciovici (2022). Effect of active learning versus traditional lecturing on the learning achievement of college students in humanities and social sciences: a meta-analysis. Higher Education. 86, 1-18. 10.1007/s10734-022-00977-8.

Lombardi, D., & Shipley, T. F. (2021). The curious construct of active learning. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 22(1), 8-43.

Wieman, C. (2014). Large-scale comparison of science teaching methods sends clear message. PNAS 111(23), 8319-8320.